Manteca’s move away from a heavy dependence on agriculture and government jobs started in the 1970s.

Spreckels Sugar was the biggest non-government employer when the decade started with 350 full-time and part-time jobs. The city had less than 10,000 residents.

Ten years later, Indy Electronics displaced Spreckels as the top employer with almost 800 workers. Indy was part of the Manteca Industrial Park that sprouted in former fields along South Main Street.

The city’s population at the close of the 1970s was pushing 21,000.

The die had been cast for Manteca’s transformation into a bedroom community for Bay Area workers fleeing pricey housing markets in San Jose, San Francisco and other areas west of the Altamont Pass.

The 1970s was a time of visionary thinking by civic leaders. The focus was on the future and how best to prepare for it.

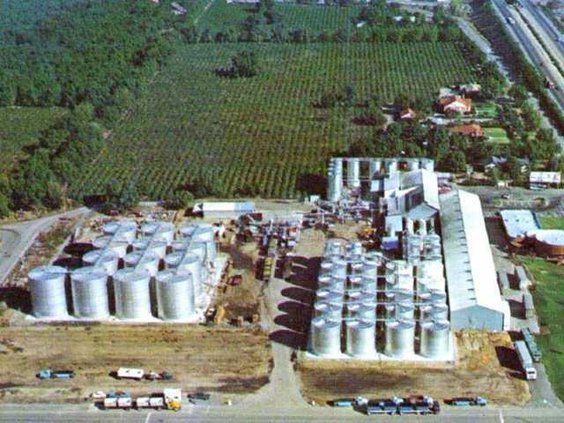

The Manteca Industrial Park was a joint effort of the city and civic leaders such as Ted Poulos and George Dadasovich. They formed an authority to purchase the land and offer sites complete with streets, water and sewer to lure businesses such as Dana Corporation and Indy Electronics to Manteca.

The Civic Center at 1001 W. Center St. broke ground. Center Street was extended from Walnut Avenue to Union Road. The city added the last nine holes to the golf course. Northgate Park was developed.

West Manteca got its first major shopping center when Kmart, SaveMart and Thrifty’s all signed on as major tenants for the retail complex at Union Road and Yosemite Avenue that has since been remodeled as the Manteca Marketplace.

But perhaps the single most defining event of the 1970s was the aggressive community campaign to lobby the California Legislature and the California Transportation Commission to build the Highway 120 Bypass.

Traffic from Friday afternoons through Sunday night in Manteca was horrific. Traffic backed up for miles as Bay Area residents trekked to the Sierra and then returned at the close of the weekend clogging up Yosemite Avenue which doubled as the old Highway 120 route.

Residents of the time reported taking upwards of 10 minutes to cross Yosemite Avenue.

Civic leaders and the Manteca City Council mobilized. They plotted a strategy to enlist the Bay Area travelers to pressure the state.

Volunteers passed out leaflets to motorists backed up at the Yosemite Avenue and Main Street traffic signal.

They appeared on radio talk shows in the Bay Area and enlisted the help of newspapers in San Jose, San Francisco, Oakland and elsewhere to editorialize the need to build a Manteca bypass.

When the CTC agreed to state funding, little did anyone know that the fight had just begun. The Caltrans design for the original bypass was a route that alternated over a five-mile stretch from four lanes to three lanes to two lanes and back to three lanes.

The result was deadly head-on crashes from unsafe passing maneuvers that quickly earned the Manteca Bypass the dubious title of “Blood Alley.” During a period of several months, the bypass was averaging one fatality a week.

Local leaders lobbied the state extensively to secure barriers down the center of the bypass to separate traffic and virtually eliminate head-on collisions.

Downtown Manteca was at the pinnacle. Clothing stores were the norm. There were two shoe stores. Storefront vacancies were rare.

The biggest controversy downtown aside from the traffic wasn’t street pavers. It was the city enforcement of its sign code.

The debate reached a crescendo when Kentucky Fried Chicken wanted to build its restaurant in the 300 block of W. Yosemite complete with its 1970s trademark sign featuring a rotating bucket of chicken.

The restaurant ended up being built with the rotating chicken bucket sign.

Moving from farming to commuting