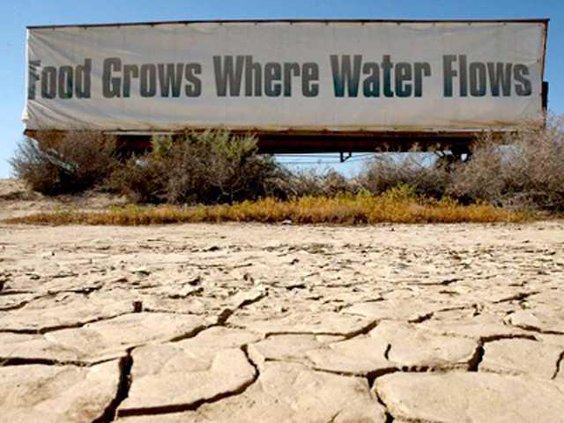

Water — or more precisely the lack of it — created a foreclosure crisis in Manteca 80 years ago that makes the Great Recession housing bust seem mild in comparison.

The drought of 1924 was the most severe on record for South County farmers nd residents. By the time it was over, almost half of the mortgaged farms in San Joaquin County were in foreclosure. The delinquent tax notices filled four pages in the Bulletin.

The lessons of that devastating drought put in motion additional South San Joaquin Irrigation District improvements that are paying off as California completes its driest calendar year on record and enters what is basically its third straight drought year.

The SSJID, unlike many of its counterparts up and down California, expects to be able to make full deliveries to its farm irrigation customers and urban users over the coming months.

That’s due to four things:

•The district’s move in 1925 to build the original Melones Reservoir in conjunction with Oakdale Irrigation to store additional water it had rights to on the Stanislaus River.

•The completion of the Tri-Dam Project by SSJID and OID in 1957.

•The SSJID’s current investment of Tri-Dam proceeds into water conservation improvements and measures at various faming operations in the district.

•The installation of the first of its kind, state-of-the-art pressurized irrigation system in the SSJID division south of Manteca and west of Ripon that has saved

The Division 9 pressurized system coupled with a three-year investment of $4.5 million to help farmers throughout the district implement more efficient farming practices has saved the district over $3.5 million so far. Both the growers’ conservation program and the Division 9 pressurized system also saved enough water to allow SSJID to net $4 million more in out-of-district water sales to other water purveyors.

SSJID leaders have made it clear the district can weather another severe drought year. But what happens if the state is hit with a fourth year of severe drought, though, is not clear although do to highest priority water rights for storage behind New Melones the district would weather it better than almost anywhere else in California.

Back in 1924 over half of the irrigated land — some 30,345 acres — were planted in alfalfa, All varieties of trees accounted for 5,076 acres. Almonds are now the biggest irrigated crop in the SSJID service territory with 33,000 acres followed by alfalfa at 6,000, grapes at 6,000, pastureland at 5,200, walnuts at 2,400 and peaches at 1,800. The rest is split between a diversity of crops ranging from corn to melons.

In 1924 the district’s lack of lined canals and the archaic farming practices of the time required 46,000 acre feet of water for a 30-minute-to-the-acre round of irrigation but there was only 36,000 acre feet on hand.

The SSJID game farmers a 20-minute run on March 19, 1924. After that was done, the district’s sole storage facility at Woodward Reservoir was completely dry as Goodwin Dam doesn’t really factor heavily into storage equations.

By the end of April, 22,000 acres had filled the 36,000-acre-foot capacity of Woodward Reservoir. That allowed a 15-minute flow per acre.

The last run of that year was on June 9, 1924 when the district released the last run-off water collected at the rate of 15 minutes per acre.

G.K. Parker, the SSJID superintendent in 1924, told the Bulletin one more run in August would have saved farmers but the district had no water.

Irrigation runs are typically every 10 to 15 days from March through October.

SSJID ready for 3rd dry year

District learned hard lessons from disastrous 1924 drought