It looms arguably as the largest ever municipal infrastructure project in Manteca history.

“It” is the fourth phase expansion of Manteca’s current wastewater treatment plant that carries a $216.8 million price tag.

And the tab will be picked up 100 percent by growth.

The need to treat sewage was the primary factor in driving voters to support incorporating Manteca as a city on May 28, 1918.

The pressing need for a sewer system was put in motion when the South San Joaquin Irrigation District started delivering water to farmland in 1914.

That set off an agriculture boom.

Within three years, the seepage of irrigation water had caused the water table to raise so high that septic tanks and cesspools — underground pits that were used to allow sewage water to soak into dirt — no longer were able to operate in the Manteca township.

The state Department of Health at one point almost imposed a quarantine on Manteca.

What the state agency did end up doing was to notify the township that if action was not taken to improve conditions the community would be taken to court.

Ed Powers — for whom Powers Avenue is named — offered to install a small system running from the downtown business section to his ranch south of the township for $3,500.

Estimates to install a complete system for the entire city came in at $20,000.

The only possible action was for the city to incorporate and then have a sewer bond election.

The first act of the new city’s council was to investigate options to install an adequate sewer system.

Contractors submitted bids in excess of $40,000.

To put that in perspective, the two-story brick City Hall building that broke ground six years later in 1923 cost $20,000. The building in the 100 block of Sycamore Avenue was recently renovated.

Also, the current “tweaking” of Manteca’s wastewater treatment projects to squeeze out more interim capacity while the city gears up for an expansion is costing $79.5 million.

By September of 1918, two sewer system proposals advanced — one for just downtown and one for the entire community.

The state approved the second proposal. A bond election took place on Oct. 29, 1918 to authorize $42,000 in debt.

A San Francisco-based contractor started work on the main lines on Feb. 14, 1919, just four months after the bond election.

Contrast that with modern-day environmental studies that can take two years or more to complete before a project can even go out to bid.

At one point, the firm was fired. The work was then completed by W.F. Edwards who was hired by the city for $10 a day for labor and $20 for the use of his equipment.

The sewer farm was located just west of Union Road where the golf course is today.

A farmer was hired at $15 a month for the pumps that spread what was raw sewer water and sewage on open fields. The city also leased surrounding land for $25 a month.

The work on the first was system was completed in 1920.

Work on ‘interim capacity’

and then a fourth phase

Today, Manteca’s sewage is treated to the point that it returns water to the San Joaquin River at a fallout west of the Oakwood Shores gated community.

The treated water is one expensive step shy of being treated thoroughly enough to meet drinking water standards.

That said, the treated water is significantly cleaner than the water it joins in the river.

The need and cost to expand the current treatment plant were identified in a 2023 wastewater master plan adopted by the City Council.

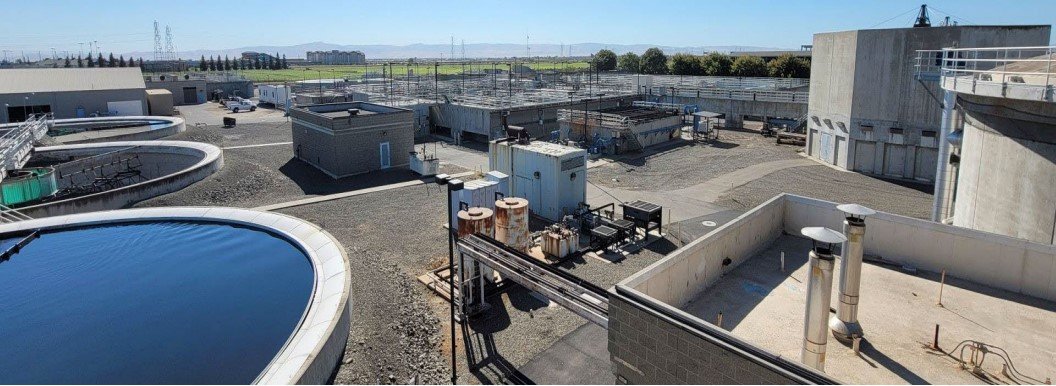

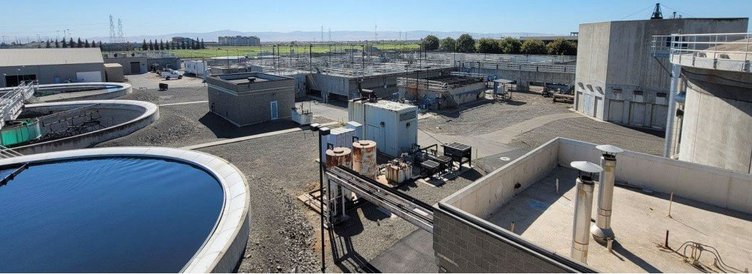

Manteca is currently involved in a project to make tweaks to the configuration to the existing plant on West Yosemite Avenue along the railroad tracks that separate Manteca from Lathrop.

The city refers to the endeavor as increasing “interim capacity” while they work on another project dubbed as the fourth phase to expand the footprint of the current facility to handle more residential, commercial, and industrial collections.

The interim capacity work is being paid for from connection fees paid by new construction.

It does not impact the general fund used to support day-to-day municipal services such as police and fire as well as street maintenance.

If and when upgrades are made for systems that are wearing out or need to be updated to meet new state standards, the funds are taken from monthly sewer fees paid by existing users.

The City Council in November 2023 was told that after completing several tweaks to the city’s wastewater treatment plant the expectation was to have enough remaining capacity to accommodate between 3,000 to 4,000 more housing units.

The plant was designed to handle a flow of 9.23 million gallons of wastewater daily.

That capacity has been lessened over the years by state-mandated changes in the wastewater treatment process.

Solid waste loading issues, however, have effectively lowered the adjusted capacity even more.

Staff in October 2023 when the revamp was first authorized, said the daily flow was between 7.3 million and 7.5 million gallons a day. The increased percentage of solids being processed due to water conservation measures is pushing the plant’s operational abilities closer to where it would be capped at 8.5 million gallons a day.

The city is working so the fourth phase expansion project is ideally timed to go online before capacity runs out.

The 1,160-page wastewater master plan notes:

*Nitrate loads and increases in salt and their required treatment has effectively reduced the design capacity of the city’s existing plant configuration.

*The current interim improvement to the treatment plant that will allow it to handle 8.23 million gallons of wastewater a day.

*A two-part fourth phase expansion will add in excess of 9.3 million gallons per day of treatment capacity. The first phase will cost $146.3 million and the second $70.5 million.

*The existing “interim” project work underway has a $79.5 million price tag and involves tweaking to the existing process to assure the city will have capacity as they gear up for the major expansion

The expansion of the treatment plant is less problematic and less extension due to the fact the original design of the current plant built in 2006 was done with such an expansion mind.

To contact Dennis Wyatt, email dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com