Here’s yet another sign of the times. The demise of family-owned dairy farm operations. In many cases, the dairy farm has been handed down from one generation to the next.

Cold statistics chronicle the sad stories – from the local, state, and national scene.

One does not have to go far, though, to get the stories. They are in and around Manteca and Ripon. They are practically right next door to us. Yes, even if you live in and around the central part of town. If you happen to live in a newer residential subdivision, chances are your house is standing on what was once a dairy farm.

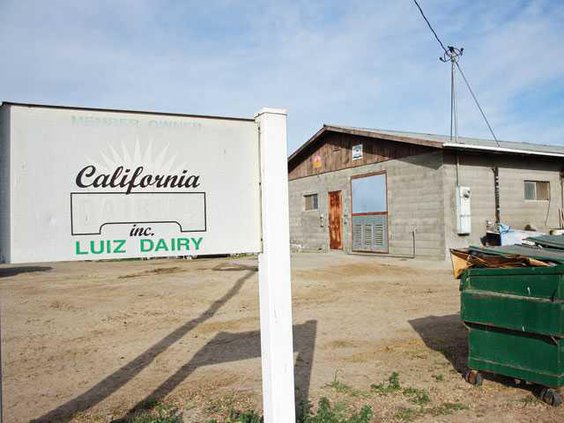

That’s exactly what’s happening at the southeast corner of Woodward and Oleander Avenues where construction is under way for the first houses in the 536-lot Oleander Estates, a project of Raymus Homes: The Next Generation. The subdivision was once the home of the Luiz Dairy. The property was sold to Raymus Homes by Melvyn Luiz who inherited and continued the family dairy after his father, who started the dairy in the 1940s, passed away more than two decades ago. A sad footnote to the history of this dairy: Luiz passed away unexpectedly at his new ranch home in Escalon right after the official signing of the property sale.

In California alone, nearly 500 dairy farms have been lost since 2008, according to Mike Marsh, CEO of Western United Dairymen headquartered in Modesto. That’s about 25 percent of large and small family-owned dairies in the Golden State. The only dairies in California not owned by families are the small dairies at the University of California at Davis, at the California State University campuses in Fresno and Chico, at Cal Poly in San Luis Obispo, and at the Corcoran State Prison.

The grim prediction is that by the end of the year, more than 100 more dairy farms in California will be lost, Marsh said.

There was a time when small family dairies were the rule rather than exception in Manteca and surrounding areas, recalled Al DeGroot. He knew several of the families with small dairies.

Today, “they’ve all gone out of business,” he said.

Some turned their dairies into almond orchards. DeGroot and his brothers who were partners in the business – Nick, Jerry, and Leo – did the same thing later on and set aside a part of their acreage for almonds.

Part of the DeGroots’ story mirrors that of the Luiz Dairy. The DeGroot brothers’ dairy and farm operation was a thriving business for about half a century on both sides of Airport Way just north of Lathrop Road. The property on the east side of the road was later turned into an almond orchard. The orchard is now part of the Del Webb community. The dairy, the farm and the cheese factory were located on the west side of Airport Way. That part of the property also has been sold. The cheese processing plant is still operating under a new name by new owners.

There was no such silver lining to some of the long-running dairies. Many of them simply auctioned off the cows and dairy equipment and closed the operation all together because of spiraling feed and operating costs colliding with low price of milk which created a perfect financial storm for disaster. That’s what happened to at least one couple in Manteca (they wanted to remain anonymous) who sold everything at auction a few years back and became part of the sad statistic in California.

Joe Brocchini remembered a time when Melton Road in rural south Manteca was practically lined with family-owned dairies. Today, there’s but one left.

“It’s hard to be a small farm anymore these days. It takes a lot of overhead and capital, plus you’re competing with a whole lot of big corporations. It’s really hard to stay afloat being a small (farming) family, very sad,” said Brocchini whose family has been, and to some extent, still continues to be a part of the area’s agricultural economy.

“It’s tough to survive” if you are a small dairy farmer, said Gary Caseri, interim San Joaquin County Agricultural Commissioner.

“A lot of times, small family dairy farmers have second jobs to help support their livelihood,” he said.

The demise of the small family dairy is happening everywhere including the town of Newman where he grew up, he noted. Every old barn you see today in his old hometown was a dairy during the 1950s when he was growing up. Those were small family dairies with 20 to 30 milking cows, he said.

Unfortunately, small dairies have “smaller ability to survive in tough economic times,” he pointed out.

High feed costs, along with stagnant milk prices, are the major factor contributing to the demise of the small-dairy industry, Caseri said.

“That has been a really big problem the last two years. Milk prices are not high enough to support the ability to pay for higher feed cost. That was a big contributing factor. There are quite a few dairies that have gone out of business (because of that). So you’re losing small dairies,” he said.

“You really have to be dedicated to be in the business. Farmers have to work hard, seven days a week, 365 days a year because cows keep giving milk,” Brocchini said. “The dairy business is not for everyone. You must be dedicated and love the hard work. But the rewards are plenty.”

Many of the early dairy farmers started with three, four cows that they bought. “Then they gradually increased their dairy herd to 900 to 1,000 cows. Modernization played a key role,” he said.

But the other part of the problem for small family dairies is that the new generation of family members “just don’t understand that they have to do hard work. Everything is given to them in a silver spoon. They’d rather play computers and videos instead of using their hands making a living.”

And that’s “the next problem,” he said. A generation getting into the world of technology “decreasing those going into farming,” he said.

While the news is bad and sad in some aspects the dairy industry, there are good news out there, like the success story of one Manteca farmer who literally started from scratch.

Western United Dairymen Mike Marsh is also noticing some good news for the dairy industry.