July is the hottest month in Manteca.

John Steinbeck, if he were alive, would probably disagree.

He’d say it was August.

Five years before the eventual Nobel Prize literature winner penned his first novel dubbed “Cup of Gold” in 1929, he spent several weeks working in Manteca.

Steinbeck’s time in Manteca was more sweat than sweet.

The author of classics such as “The Grapes of Wrath”, “Cannery Row”, and “East of Eden” labored at Spreckels Sugar in August of 1924,

Steinbeck worked on Spreckels Sugar’s Coastal Empire ranches and plant laboratory around a wide spot in the road known as Spreckels, just three miles south of Salinas, that served as his inspiration for “Tortilla Flat.”

He was sent to Manteca to work in the Spreckels plant that once stood right around where the Target Store is now along Spreckels Avenue.

He boarded in the Spreckels Club House, located where the 177-home Curran Grove neighborhood was built. Curran Grove, by the way, was named after a popular manager at Spreckels Sugar.

Steinbeck worked 12-hour days in the warehouse stacking 100-pound bags of sugar before moving to the factory where he worked on the melter station.

Steinbeck’s famous temper did not take too well to working long hours in the valley heat. He ended up getting in a fight.

His time in Manteca as a “sugar tramp”, the name given sugar beet workers that moved between plants within the Spreckels Sugar empire, was long before he was known enough for anyone to write down words he may have said.

That said, as Steinbeck found his literally footing years later, several plant workers who remembered him were quoted as saying he quit and headed back toward the coast and cursed Manteca for being “too damn hot.”

Whether that quote is true, it is a sentiment shared by many since — and even today — that venture east over the Coastal Range from places like the Bay Area as well as the Salinas Valley where the high Thursday was 24 degrees cooler.

A look in the rear view mirror as Steinbeck returned to his beloved Salinas Valley and the Monterrey Peninsula where he found his footing as a writer, was indeed east of Eden as far as the Salinas native was concerned

While Steinbeck’s stint at Spreckels Sugar helped shape his voice when he started writing books, the wealth processed from sugar beets in Manteca, Spreckels, Mendota, and other plants, such as the one near Clarksburg in the Delta helped build San Francisco.

It is where Claus built his mansion that covered a city block on Nobb Hill that one day would be owned by prolific novelist Danielle Steele.

Spreckels made major contributions to the city’s culture.

They ranged from the Spreckels Temple of Music in Golden Gate Park to his greatest gift: The California Palace of the Legion of Honor art museum.

It is commonly referred to today as the Palace of Fine Arts.

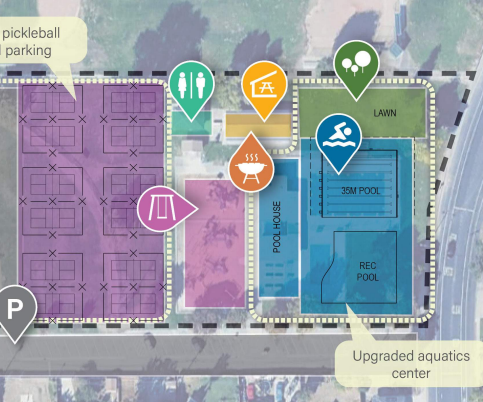

As for the present day heat with all the angst that somehow man has replaced the forces of nature in terms of steering climate change, you can now lallygag in the area where Steinbeck sweated buckets.

It will be in an air conditioned Target partially powered with solar panels on the roof to put the unforgiving San Joaquin Valley mid-day sun to good use.

Steinbeck, who died in 1968, wouldn’t have been too surprised to see where modern retail has gone.

He might be amused that the sugar factory with its heat generating boilers, the often wretched smell of sugar beet pulp, and dusty grounds is now a retail Mecca of sorts where shoppers are oblivious to the back breaking manual work that was once needed to survive in the San Joaquin Valley.

He’d likely be disappointed that what passes for a book section at Target today is devoid of any work that uses fiction as a sounding board to reflect the real world struggle of good and evil.

And he might wonder what happened to the sugar beet industry that at one time constituted one of California’s biggest business enterprises ever.

Spreckels Sugar lasted for another 28 years after Steinbeck’s death, ending the run of a storied corporation credited with giving life to San Diego and having more influence in Hawaii in the 1880s than King Kalakana.

As funny as it might seem, tariffs — along with price supports — helped protect hundreds of factory jobs in Manteca and significantly more in farms raising sugar beets.

Sugar, since the dawn of civilization, has been viewed by nations as a strategic commodity.

A brief period from 1974 to 1981 when federal government interference on the sugar market dropped considerably, prompted a decline in domestic sugar production that is now concentrated in Texas and parts of the South.

Spreckels pulled the plug on its Manteca plant in 1996.

Holly Sugar in Tracy followed several years.

And now the last sugar beet refinery in California, that also happens to carry on the Spreckels name as a subsidiary of the Southern Minnesota Sugar Beet Cooperative, is closing for good this summer.

The refinery in Brawley in the Imperial Valley is likely to signal the demise of the California sugar industry that was once the largest in the states.

Last year, sugar beet production had dribbled down to $500 million out of $60 billion in overall agricultural crop output.

Hawaii’s commercial sugar production from sugar cane went belly up nine years ago.

The reason for the closures is a broken record.

*New air quality regulations making it prohibitive to modernize aging plants.

*Raising labor costs.

*Foreign competition.

The reason sugar beet production survives in Texas, the South, and Midwest is due to less expensive labor and less stringent air quality regulations.

Even so, if it weren’t for tariffs that control the flooding of the American market with cheap sugar, there would be no sugar production left in the United States.

The tariffs are two-tiered.

It is built on allowing “x” amount of sugar in to prevent domestic prices from going too high.

A sliding tariff schedule at the same time helps prevent the demise of domestic sugar production.

Tariffs below the annual quota are currently at 0.125 cents a pound.

Sugar that exceeds the quota is slapped with a whooping 24.09 cents per pound tariff.

The rationale is it to keep prices in a zone where it doesn’t overburden consumers while at the same time protecting domestic sugar protection.

As such, it avoids the United States from becoming 100 percent dependent on other countries for sugar.

Such nuances don’t strike people as important.

But it is in a world where food security ranks right up with energy security, and water security are the bedrock of a nation’s economic viability and ability to function.

This column is the opinion of editor, Dennis Wyatt, and does not necessarily represent the opinions of The Bulletin or 209 Multimedia. He can be reached at dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com