What would you call someone who sat on a $700 land investment for 55 years and then used it to cut a deal to generate $73,478 in annual net income that has the potential over 55 years to generate $4,041,290?

Words such as astute, long-range thinking and smart come to mind.

Those are words that not too many people would use to describe the City of Manteca.

But given what they did Tuesday if you are one of the city’s unforgiving critics that are correct to seize on the craziness that can originate at 1001 West Center Street you might want to concede that there have been times over the last 30 years or so that city leadership has been crazy like a fox.

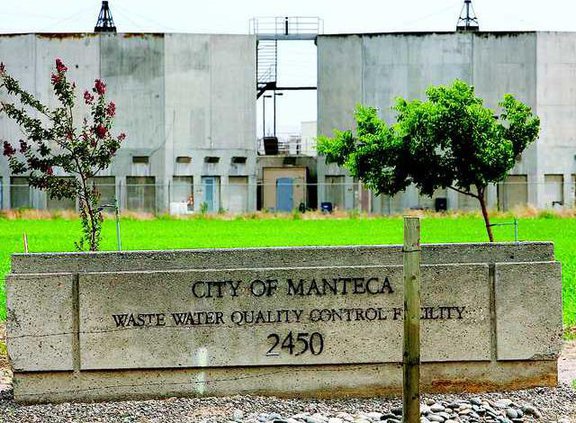

That is especially true of what the city has done to date with land that most developers would literally turn their noses up at — acreage the city originally bought over a half century ago for treated wastewater disposal spray fields.

Looking toward the future in 1966 as Manteca started growing, the city padded its land holdings for future spray field use by 56 acres at a cost of $34,333 or just under $700 an acre.

At the time plant smell and state disposal requirements made it a sound decision so the “new” treatment plan wouldn’t have its life shortened as the previous one did on Union Road.

That treatment plant eventually became the back 9 holes of the Manteca Municipal Golf Course. The front 9 holes and the clubhouse, by the way, sit on the site of the former municipal dump.

Evolving technology eliminated plant odors and made treated wastewater clean enough to the point that it not only can be returned safely to the San Joaquin River but it is actually cleaner than the river water it is joining.

Fifteen years ago, after the city leadership headed by then Mayor Willie Weatherford on the elected side and then City Manager Bob Adams on the bureaucracy side resolved the push back against locating a Big League Dreams sports complex at Woodward Park to make it financially feasible to turn 52 weed infested acres into high intensity recreational uses, by recommending it be built instead on land no longer needed for the wastewater treatment process, someone had an epiphany of galactic proportions.

The city — between the 1966 purchase and land acquired beforehand for the treatment plant — was sitting on a municipal Mother Lode.

They had more than 120 acres that were no longer critical to the operation and future growth of the treatment plant due to cutting edge technology they used in the last upgrade that allowed the city to be among the first in the region to meet extremely high state standards to return treated water to the river.

It sat on top of an interchange — Airport Way — that had no development around it including subdivisions. Plus it had freeway exposure to the heavily traveled 120 Bypass that funneled both Northern San Joaquin Valley commuters back and forth to the Bay Area as well as Bay Area residents to back and forth to Sierra recreation destinations.

They made two key decisions. They parlayed the huge jump in redevelopment agency bonding capacity made possible by the conversion of the shuttered Spreckels sugar beet plant into a dynamic 362-acre multi-use development to build the $29 million BLD complex plus build the initial extension of Daniels Street west of Airport Way. That not only provided access to the BLD complex but it opened up land to develop the Stadium Retail Center originally anchored by Mervyn’s and allowed the city to snare Costco.

They also hedged their bets by tapping the sewer fund to buy 220 acres some two miles to the south along Hays Road. Its purpose was simple. If the state’s ever changing rules forced a return to even more robust land disposal of treated wastewater the city wouldn’t be caught flat-footed. All it would need to do would be to extend a pipeline.

Tuesday’s deal the City Council approved involving a 55-year land lease for 36,560 square feet — 7,060 square feet shy of an acre — with Loma Brewing Company to locate at the BLD site along Daniels Street near Milo Candini Drive is the end result of the city’s decision to buy 56 acres for less than $700 an acre back in 1966.

The land was appraised at $62,000. The city was able to legally “discount” the land under state law due to a significant positive economic impact it would create for city coffers to fund day-to-day municipal services as well as general overall economic benefit to the community in the form of 40 to 70 jobs.

The $22,000 annual rent discount is being taken from projected sales tax.

It still leaves $40,000 a year in land lease payments flowing to the city. The overall $62,000 starting annual land lease payments will escalate every 10 years through the duration of the 55-year contract. Based on the initial full year sales tax projects the city would receive of $30,992 the city would net $8,992 after the “rebate”. When added to the $40,000 “net” from the land lease that comes to $48,992 flowing into the city’s general fund after the first year.

Taking the city’s share of sales tax projections on the fifth year of operations with the brewery up to 100 percent capacity, the city’s share of sales tax would hit $55,478. Delete the $22,000 rebate and that’s $33,478. Once you couple that with the $40,000 land lease net and the city is seeing a positive cash flow of $73,478 annually.

For ease of calculation ignore the lease increases and inflation impacting prices and sales tax receipts. Over the course of the 55-year land lease the city will net $4,041,290 from an initial investment of less than $700 in 1966.

In a best case scenario and assuming the 80 or so remaining acres of city owned land within the family entertainment zone are all land lease deals, the FEZ concept could generate in excess of $300 million in city revenues over 55 years.

That does not include the 30 acres sold to Great Wolf to land the $180 million 500-room indoor waterpark resort opening June 29.

Over the course of its first 30 years the city will net $74.3 million or an average of $2.4 million a year.

And when the room tax sharing with Great Wolf goes away in the 31st year meaning every penny on room tax collected at the resort goes to the city, Manteca could see a net of $90 million from Great Wolf.

That means a $35,383 land deal combined with savvy forward thinking and long-term investment strategies executed under the watches of city managers such as Richard Cherry, Dave Jinkens, Bob Adams, Steve Pinkerton, Karen McLaughlin, Tim Ogden, and by whoever was minding the store in the last six months or so when the Loma Brewing Company deal was hammered out will push a $390 million return.

Toss in the cost-avoidance in terms of maintenance and upkeep the city realized by leasing out the sports complex to BLD to the tune of $16.9 million for the first 35 years and the net positive impact on the City of Manteca soars past $400 million over 55 years.

Given the city is dealing with 80 acres acquired in or before 1966 that represents a $5 million return per acre over the next 55 years for land that cost $700 per acre.

This column is the opinion of editor, Dennis Wyatt, and does not necessarily represent the opinions of The Bulletin or 209 Multimedia. He can be reached at dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com