The defining moment of the Flood of 1997 was a husband and wife being interviewed by a KCRA-TV reporter.

They were standing in the back yard of their home in Weston Ranch.

The cameraman minutes earlier filmed their neighborhood street where driveways were filled with Ryder, U-Haul and other rental trucks.

Families were scrambling to load valuables and heirlooms.

It was a scene repeated throughout Weston Ranch as well as Lathrop.

A day earlier, the state Office of Emergency Services advised residents to be prepared in the event an evacuation was ordered.

Rental companies reported every available truck in Northern California had been rented and sent to South San Joaquin County.

They even pulled in trucks from Northern Nevada and Southern Oregon.

Crews were monitoring a number of boils along the bank of the San Joaquin River near where it passes under the Interstate 5 and Mossdale Crossing bridges.

The boils, bubbling water making its way through the ground on the land side of a levee, are a precursor to a potential break.

The boils ended up being contained successfully with sandbags.

It would still be days, however, before the danger ebbed.

Now let’s go back to the TV interview.

The reporter asked the couple if they were worried about their home getting flooded.

As the man started to reply, the cameraman panned the yard behind the couple.

“If we had known this was a flood zone,” he said. “We never would have bought our home.”

Before he finished speaking, the viewers were able to see a 20-foot high or so levee behind them.

The obvious question that the reporter did not ask: What did they think the levee behind them was for?

If one is buying a house that backs up to an earthen wall separating it from water, wouldn’t they think to at least wonder why it is there?

In fairness to the couple, they are no different than everyone else.

Levees don’t fail every day.

People live in areas protected by levees.

That said, levees have the potential to fail.

To their credit, property owners in the 200-year floodplain that was identified in South San Joaquin County in the deadly aftermath of Hurricane Katrina in 2005 stepped up 18 months ago by a margin of more than 75 percent to tax themselves.

That will cover part of the $475 million tab to make flood protection more robust from a 1 in 100 chance of happening every year to a more catastrophic event that has 1 in 200 odds of happening in any given year.

If you are a homeowner in the 200-year-old flood plain the size of the annual assessment is based on the elevation of property with those at greater risk and those at a minimal risk being charged accordingly.

The bottom line was simple: If 200-year flood protection is not put in place, homes with mortgages would be required by the Federal Emergency Management Agency to buy expensive flood insurance with $15,000 deductibles with coverage capped out as low as $250,000.

Even if one owned their home free and clear, the flood insurance requirement would devalue your property when you went to sell because a buyer needing a mortgage would be saddled with that additional cost of home ownership.

The need for 200-year flood protection was also underscored by California Senate Bill 9.

That requires the various areas in the state in 200-year flood zones to have upgraded protection in place by 2030 or be at a point where construction is underway or imminent.

If not, there can be no new construction or work that expands beyond existing footprints of structures.

The coordinated efforts of the cities of Lathrop, Manteca, and Stockton along with San Joaquin County through the organization they formed — the San Joaquin Area Flood Control Agency — is on track to make sure that won’t happen and assure that existing homeowners aren’t saddled with flood insurance policies that cost a minimum of $2,200 a year on top of regular homeowner insurance.

Perhaps the biggest lesson from 1997 was the assumption that the State of California would actually do something about the levees in the Delta.

Many levees still protecting rural areas were created from nearby materials that aren’t necessarily the best choice.

The 11 breaks in the levees south of Manteca that led to 70 square miles being flooded between Manteca and Tracy 29 years ago is operated by a typical non-urban reclamation district.

That means they often lack funding needed for more robust projects and have to settle for what are essentially patches.

It may surprise you, but in flood-prone California levees are a local and not a state issue.

As such, the California Legislature for decades danced around the issue given voters have a tendency not to understand why you are taxing them to build more robust levees in the middle of a drought or when it is 100 degrees.

The state did act after the 1997 flood.

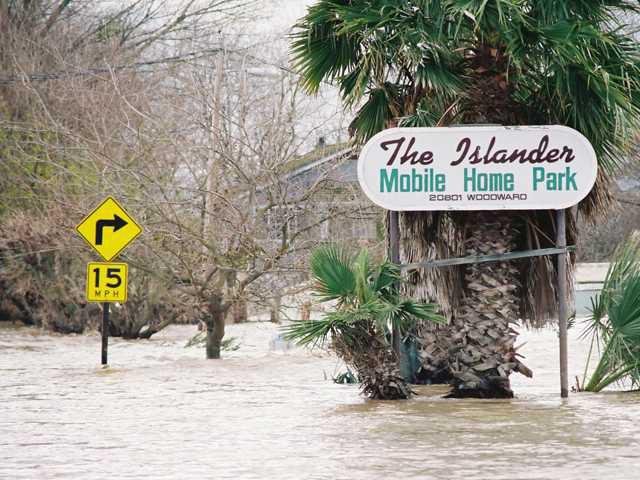

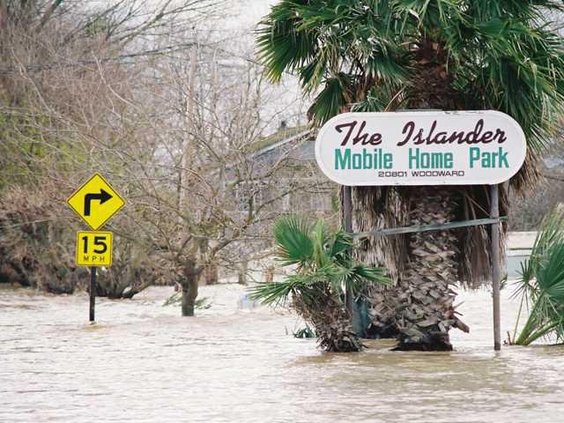

Given people with memories of how areas such as homes in Weatherbee Lake at the end of Woodward Avenue were under water for nearly two months, politicians had to look like they were doing something.

They cobbled together a statewide bond measure in 2000 that included $10 million to study whether there was sediment buildup from not dredging they San Joaquin River channel.

The idea was if that could be proved — especially given runoff from the Westside for decades was dumped back into the river — dredging would create volume for more water to flow.

The study was never done. The money was spent elsewhere.

If it wasn’t for FEMA being directed by Congress after Katrina to assess the vulnerability of levees nationwide that determined the top candidate for Katrina 2.0 was the Sacramento-San Joaquin Delta, the state legislature likely would never have passed Senate Bill 9.

Taking reasonable precautions that can be expensive unfortunately isn’t something to do unless your hand is forced.

Nor is looking around your own backyard and realizing there are vulnerabilities staring you in the face.

At any rate, thanks to the coordinated SJAFCA effort, the odds of South San Joaquin avoiding the fate of New Orleans are being reduced substantially.

This column is the opinion of editor, Dennis Wyatt, and does not necessarily represent the opinions of The Bulletin or 209 Multimedia. He can be reached at dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com