Alice Smith rummages through boxes in the garage, searching for a photo of a long-lost relative she’s never met.

His name is Duke, and he was a war hero not unlike her husband Art Smith.

In fact, the two were partners ... buddies ... brothers in a bloody war fought over a two-decade period in the jungles and swamps of Vietnam.

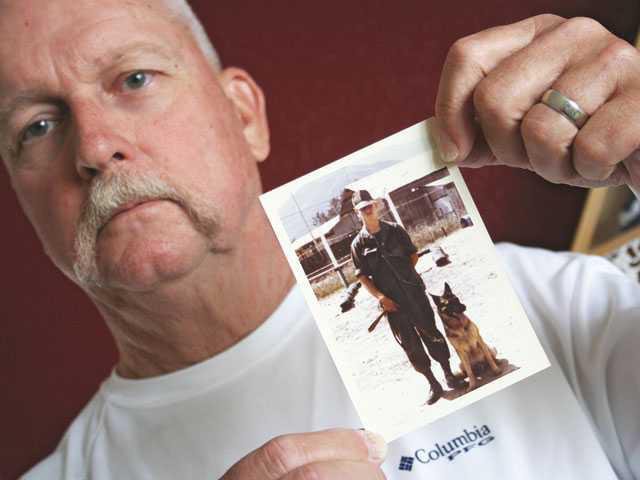

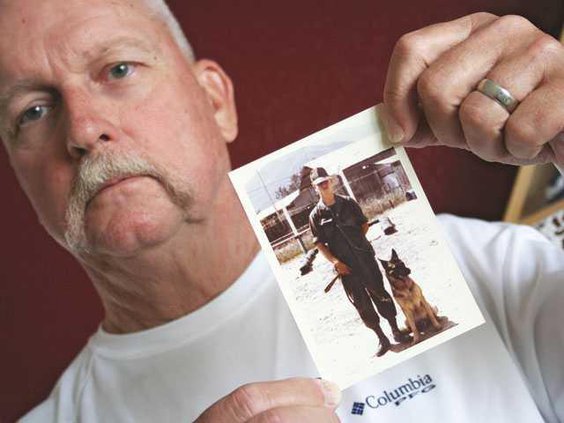

“Here it is,” Alice says, producing a picture of Art and Duke and another of Art by himself outside his barracks in Georgia.

The buddy photo is creased in the corners and yellowing from years stuck in a frame or a pocket. But even with all that wear and tear, it tells its story well.

Art is dressed in green jungle fatigues, pants tucked into tall black boots, with a hat pulled low on his brow. “He was young,” Alice chimes in. His shoulders are square – like his jaw.

At his side, sitting equally as stoic and strong is Duke, a German Shepherd.

Art rubs his gray handlebar mustache two and three times over. His cheeks grow red as the story turns toward Duke and the time they spent trekking about war-torn Vietnam. His lips quiver as the memories wash over him.

“We went where we were needed,” said Smith, a sentry dog handler and drill sergeant in the U.S. Army from November of 1969 to January of 1972. “We were all over the place.”

And mostly out in front of the action.

Art and Duke were the very tip of the sword, tasked with scouting positions, tracking the enemy, guiding teams of soldiers and keeping watch through the night.

They were paired together randomly back in the States, but went together like hand in glove in the field. They operated in silence with Duke obeying his handler’s hand signals and Art paying close attention to his sidekick’s every twitch and movement.

“At night, I’d watch his ears,” he said.

They were stealthy and dangerous, cunning and intuitive – essential skills for a position with a low survival rate. When he volunteered for the job, Art was told only six in a class of 44 future dog handlers would come home intact. The others would return injured or in a pine box.

No matter. He loved his country and he loved dogs. There would be no finer way to serve both, he thought.

“We relied on dogs a lot because they can see, smell and hear far better than any human,” Art said. “(Soldiers) felt more comfortable with dogs because they felt like they had an extra safety net.”

This part of the story is the most draining on Art, a retired employee with the Board of Prison Terms and friend of the Manteca Police Department’s K-9 unit.

He sits near the edge of a chair in his living room, pictures of his adult sons decorating the book shelves behind him. Alice, his wife of 40 years, sits in the other room.

Their 34-year-old home has that brand-new smell courtesy of fresh paint and new carpets.

Art rubs his hands together, apologizing for any hint of the fish he caught and cleaned earlier that day.

If it weren’t for Duke, Art says, none of this would have been possible. If it weren’t for Duke, his would have been a name honored and celebrated on a cross or wall this Memorial weekend.

Simply: Duke gave him a chance to experience all of life’s wonders – marriage, fatherhood, career and sport.

“I relied on him to tell me if there was an attack on the post. He was my life vest. I put all my trust in that dog. He’s why I’m here today. He let me know if they (enemy) were there. Without him, I’m no longer here.”

Art came home.

Duke did not.

Because of his extensive training and experience in the field, the military found Duke unfit to become a pet. Officials were confident Art could transition to civilian life, but his four-legged companion was a trained attack dog that had been exposed to too many diseases.

The 2-year-old German Shepherd was euthanized.

Art mourns his death each and every day. He honors Duke’s life with a sticker on the back window of his truck.

He’s taken their experiences in training and combat theatre and applied them to civilian life. He’s trained German Shepherds as guard dogs and developed hunting dogs, including “Duke,” a yellow Labrador named after his ol’ military hound.

“He’s so smart,” Art said of his lab. “He’s a reincarnation.”

Art’s transition hasn’t been as seamless or smooth as many thought. All these years later, the dual member of the American Legion Post and Veteran of Foreign Wars still struggles with nightmares and flash-backs.

The sounds of a helicopter or fireworks overhead have knocked him out of bed. For a long time, he couldn’t stand to be in a crowded room; the thought of someone standing behind him made him paranoid.

If Duke saved his life, Alice taught him how to live. They began dating while he was working a transitional job at Sharpe Army Depot. She kept him busy, filling his free time with food, family functions, camping trips and other getaways.

A descendant of career military men, Art found the silver-lining in Duke’s unfortunate death.

“I’m grateful,” he says. “I came back. Brock Elliott, Jack E. Landers and all those guys never had a chance. They’re dead.”

With that thought, Art begins to count his blessings on his fingertips: Marrying the love of his life in 1973; watching the births of his sons, Jason and Eric, and becoming a family man; teaching his kids to ride a bike; and watching them play sports, go to school and eventually marry.

“I’m grateful because I got to do all those things,” he says. “That’s why I do the troop packing events and the (Never Forgotten) cross project.

“I remember when we used to get one package for like 40 guys. You’d cut it open and 40 guys would eat out of it until it was gone.”

Forty guys and a dog named Duke.