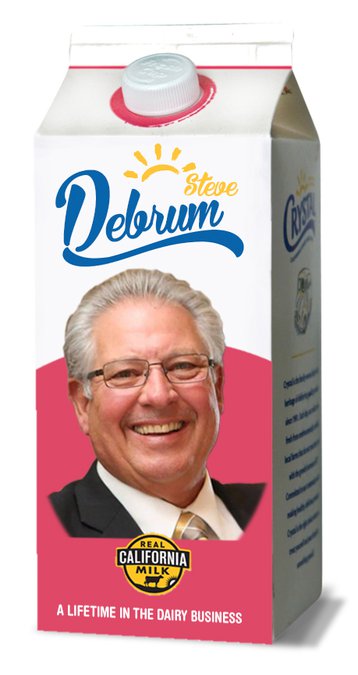

Got milk?

Rest assured Steve DeBrum’s refrigerator is stocked with it.

DeBrum — Manteca’s mayor — ended a 48-year career in the dairy industry on March 23 that ran the gamut from running a dairy, overseeing a dairy lab, producing everything from cottage cheese and milk to cheese, serving as a co-op field representative maintaining quality control and public relations with farmers, to overseeing dairy co-op partnerships in Northern California and Nevada.

But in reality he has spent every one of his years around the dairy industry whether it was growing up on his father Larry’s dairy farm in Hanford and helping milk the 260-head herd or majoring in dairy sciences at Cal Poly at San Luis Obispo.

“My first job (at the family dairy) was as a 6-year-old in charge of the water hose,” DeBrum said.

Milked his first

cow as a 10-year-old

He milked his first cow as a 10-year-old. His father and uncle during the school year would get up for the 4 a.m. milking and then handle the milking again at 4 p.m. — a process that took over 4 hours each time in their 32-cow milking barn. DeBrum would get up at 5:30 a.m. and handle the feeding and other chores before heading off to Hanford High.

His senior year DeBrum was the Hanford FFA chapter president while his future bride Veronica was the FFA chapter sweetheart. Both graduated in 1965 and celebrated their 50th wedding anniversary last month.

DeBrum said those who dismiss agriculture as not being an industry you can make a good living and have a fulfilling career pursuing do not have a grasp of the dynamics farming involves and the number of head of household jobs agriculture supports.

DeBrum noted all farmers — from dairymen to almond growers — have to be well versed in sciences, nutrition, stewardship of water and the land, wise users of water, strong in economic matters, and always open to using cutting edge technology to increase production.

Back in the 1960s in the heyday of his father’s dairy the industry norm for daily cow milk production was 3½ to 4 gallons of milk a day. Today it is between 10 and 10½ gallons.

An avid milk drinker

even at age 71

And you’ll see DeBrum drinking his fair share of that milk production.

“Some days I’ll have two glasses of milk,” DeBrum said noting his favorite has 2 percent fat.

He added if he could never have milk again, the biggest thing he’d miss is “having something to pour over my cereal”.

That said his favorite dairy product is ice cream.

And he’s says nothing is better than maple nut ice cream that you can get from the Superior Dairy in Hanford.

“You order a sundae there and you get huge scoops of ice cream,” DeBrum said.

But if you ask DeBrum about his favorite childhood memory of ice cream, it revolved around a visit to a store in Kingsburg his family stopped at after attending their parish church in that community. Their family farm was 8 miles from Kingsburg and 11 miles from Hanford.

“They sold half gallons of ice cream for 99 cents back in the 1960s,” DeBrum recalled. “We would buy a number of them each week.”

Going to work for California Cooperative Creamery — forerunner of Dairy Farmers of America that he worked for during the last 34 years — is what brought him to Manteca in 1984.

He landed his first dairy industry job with Foremost after college while working on a farm. He continued working on the farm for a number of years while getting hands on experience making everything from cottage cheese to cheeses. He also packaged various milk products that included carton switches given that many of the brands that have graced store shelves over the years are often processed through the same plants.

Foremost eventually assigned him to their lab that — along with field representatives working with farmers — is responsible for the critical science that assures everything a dairy firm sells to the public meets high and exacting federal standards.

‘If you keep milk

cold, you’re fine’

“Milk is one of those foods that stay fresh for a long time,” DeBrum said. “You can use it eight days past the expiration date.”

But there is a caveat to that. Expiration dates aren’t the date that a food product goes bad. It is designed as a date that something should not be sold past to assure freshness.

Where things sour quickly is how people handle milk after they buy it.

DeBrum shared how during presentations about milk to school-age children he’ll talk to them about putting milk on their cereal.

“I always ask them whether they put the cartoon back in the refrigerator right after they pour their milk,” DeBrum said. “They usually say they don’t.

Leaving milk sitting out can compromise its life.

“If you keep milk cold, you’re fine,” he noted.

DeBrum noted organic milk is a good niche product but that some people have the wrong idea about antibiotics and hormones.

Milk from cows can’t be sold for human consumption until it tests free of any traces of antibiotics.

Antibiotics, DeBrum noted, are used to combat cow illnesses just as they are in humans.

As for hormones, DeBrum said there is no such thing as a cow without them.

“We have hormones, animals have hormones, and cows have hormones,” he said.

DeBrum ended up finding his niche in the industry when Foremost promoted him to field representative in 1976 to work with 113 dairies in San Luis Obispo, Kings, Fresno, and Tulare counties. It was three years working as a Foremost field rep that he found he loved the troubleshooting aspect to make sure stringent quality control was always maintained as well as the public relations aspect of working with farmers.

He spent several years running a dairy after that before settling into 34 years working as a field rep and then an area manager where he oversaw other fields reps will working directly with 24 dairies.

DeBrum noted not only is owning and running a dairy a seven day job 24/7 a year given the cows have to be milked twice a day on their time and not yours, but the need to constantly find ways to increase production while keeping costs in check can be a challenge. It is not unusual for milk prices paid to dairies to drop below what it costs them to produce for long stretches of time.

Dairymen can’t simply stop producing milk when prices drop.

When DeBrum started out California had 2,500 dairies. he now says the number is about half that. Small dairies are essentially history while larger operations with cows ranging from 3,000 to 10,000 are now more common.

It is against that backdrop that it surprises more than a few people that California is the No. 1 dairy state and not Wisconsin. That’s based on production and the number of cows.

California in 2016 had 1.7 million cows compared to Wisconsin at 1.2 million. In third was New York with 620,000 cows.

DeBrum noted that any food placed on your table — and a lot of clothes on your back that have cotton — were made possible by farmers.

“My favorite bumper sticker is “Don’t talk bad about a farmer with your mouth full,” DeBrum said.

To contact Dennis Wyatt, email dwyatt@mantecabulletin.com